A March Against Consumerism.

Our rehearsal process began when we were asked to think about what the word “liberation” meant to us. I personally associated the word with freedom, release and rescue. We chose Lincoln high street as our site and decided to focus on consumerism and the public’s everyday routines. We wanted to liberate the public from the modality of consumerism through human interaction by disrupting the public’s everyday routines in order to give them a sense of release and freedom. Our performance began at 11am on the 7th May on the Lincoln high street and ended at 1.30pm. We created four A2 signs that had the following written on them: “Can we hug?”, “Can we high-five?”, “Can I compliment you?”, and “What would you write?”. The signs were propelled upward onto large wooden poles so we could be seen from very far away. We placed ourselves with each sign from one end of the high street to the other, so we were in each other’s line of sight at all times. Every half an hour we would swap our signs with one another by marching to the centre of the high street which for us, was the archway. This was the formal aspect of the performance in order to emphasise the importance and underlying seriousness of what we were doing. We were inspired by the Queens Guard ritual procedure which we referred to in our performance as, the ‘March of the Guard’ and to ensure we were on time with one another, we wore synchronised watches. Our key ideas for our performance were influenced by the works of Guy Debord and the situationists and so this was our main source of research.

(Taken 7th May 2015, Lincoln High Street).

The City

Firstly, site was an extremely important aspect of my research and for this, I decided to research the city, the people who inhabit the city and explore the differences between consumers and non-consumers in the city. According to Foust and Jones, the city “accommodates a diverse array of consumer performances, while the presence of non-consumer others […] is outlawed or more subtly policed” (Foust and Jones, 2008, 4). In the city, consumerism is considered a social normality and so non-consumers are perceived as the other who doesn’t belong. Walking through the city as a non-consumer is seen by the majority as interrupting the systematic flow of commercialism. This is precisely what we aimed to do through performance. Our aim was to disrupt the flow of consumerism, even if it was for a fleeting moment in order to give the public a sense of release and freedom. The non-consumer cannot help but feel alienated due to the fact that the people around them are all abiding to the social normalities of city life. In this case, the “consumer subjects are ‘in place,’ performing ‘properly,’ and (for the most part) complementing, rather than interrupting, each other’s performances” (Foust and Jones, 2008, 9) and when the non-consumer does not perform according to these ideals, they are seen as a threat to the system. They threaten to disrupt the regulated structure of consumerism by challenging the ideology behind it. Taking these ideas into consideration, I decided to walk through the city as a non-consumer. Walking through Lincoln high-street, I became aware that I was observing things that I had not noticed before, and I was especially aware of others around me. I also felt separated from others but strangely liberated because unlike the public around me, I was walking aimlessly, without purpose which felt very alien to me. Walking up steep hill, I found this loose brick that had come away from the path and I had the urge to put it back where it belonged which made me think about how some things are deemed ‘out of place’, much like the non-consumer in relation to the high street, where it is the normality to spend money.

(Taken 14th March 2015, Lincoln High Street).

The city itself has the “potential to stage interruptions and challenges to consumerism” (Foust and Jones, 2008, 5) and by using separation as the distinction between consumer and non-consumer enables us as a society to take a closer look at the influence of commercialism. We wanted to give the public a chance to feel liberated from the constraints of consumerism by disrupting the ‘natural’ flow of modern city life, even if it was for a fleeting moment. Looking at our performance from a political point of view, we were ultimately challenging the ethics of consumerism. To add to this political slant on our performance, it was Election Day and so our signs may have been mistaken for being party political, however this was not the case. When the spectators realised that we were not promoting a political party they became more interested and may have even felt a sense of release from tension at our more innocent, simple gesture. Signs are commonly used for advertisements and our ‘misuse’ of the sign, challenges the politics of consumerism because we were using the means of advertisement to offer something which has no price. We were making a stand against money making schemes by using the very means that support it.

Consumerism

During our performance process, I focused mainly on the work of Guy Debord and the situationists because their work showed many parallels to the piece we wanted to create. In Debord’s Critique of Separation, he suggests that “we don’t know what to say. Words form themselves into sequences and gestures recognise each other” (Debord, 1992, 43). Debord emphasises that we have lost the means to communicate on an authentic, honest level and argues that the words we use to form sentences are produced by our sense of political correctness. We are afraid to push the boundaries of what is deemed as politically correct in case we are unaccepted and seen as other. Debord continues to question the fundamental aspects of communication when he asks “what communication have we desired, or experienced, or only simulated? What true project has been lost?” (Debord, 1992, 43). Debord suggests that we desire more intimate, authentic communication on a personal level that will actually satisfy our need for social interaction. The ethics of Debord’s theory is what inspired the ‘hug’ and ‘high-five. We replaced words with physical gestures in order to emphasise the importance of human interaction and to create a spectacle using intimate, personal gestures.

(Taken 7th May 2015, Lincoln High Street)

Debord continues to analyse our need for authentic social interaction by suggesting that dreams are a product of our unfulfilled desires. In Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, he states that dreams are the “royal road to the unconscious” (Freud, 1997, 64) and that at the centre of each dream is a repressed wish. Debord, being influenced by Freud’s dream-work theorises that dreams “strikingly publicise those of our needs that have not been answered” (Debord, 1992, 47). Debord emphasises that our repressed desire for authentic social communication is presented to us through our unconscious in the form of a dream. Freud also theorises that every dream once analysed thoroughly can be seen as a wish-fulfilment, however, these wishes may conflict with our responsibilities and conscious aims. In this case, our wish to connect with one another through different, bolder means of communication and interaction conflicts with society’s ‘normal’ way of communication. In our performance, we wanted to break boundaries and offer gestures that are not normally presented to strangers in order to create authentic social interaction. We did an experiment to see what kind of reaction we would receive from the public in which we stood in the middle of Lincoln High Street and held laminated pieces of A4 paper that had ‘Can we high-five?’ written on them. This is the video evidence from that experiment:

(Taken 16th March 2015, Lincoln High Street)

The public genuinely looked eager and curious to find out what we were doing and why. For instance, in this video, I had a conversation with two men which went like this:

Man: “What is this for?”. I then gave a brief explanation of what we were doing, explaining how we were trying to create social interaction with strangers in order to interrupt the flow of consumerism. Man: “That’s awesome! Who has even said no yet? Let me find them and hunt them down for you” *Laughter*. “You’ve brightened my day”.

We were extremely happy for this type of reaction because rather than just high-fiving strangers, we were able to give them a reason why we were doing this without the need of forcing the information on them. They were genuinely interested and willing to hear what we had to say which made for us a successful experiment.

I researched more into the situationists and according to Sadie Plant, situationist theory is “the unified study of spectacular society” (Plant, 1992, 4). The situationists explore concepts of futurism, Marxism, Dadaism and Surrealism in order to invoke “a wider world of meanings which challenged conventional arrangements of reality” (Plant, 1992, 3). The ‘reality’ Plant refers to here, represents capitalist society, thus she suggests that the situationists challenge the structure of capitalist society in relation to the individuals who are forced to abide by these codes. This concept made me think about the politics of our performance and how we are challenging the boundaries of consumerist society by creating a spectacle that subverts social codes and regulations. Debord is especially interested in Marx’s theory of alienation which “refers to the subjective or objective state of the individual in capitalist society, a state categorised by desires which are either distorted or frustrated, and by a lack of understanding and control of the social environment” (Elster, 1986, 29). Debord focuses on the way individuals are alienated from themselves, their own emotions, experiences and desires due to the constraints of capitalist society. In our performance, we closed the gap on separation by introducing gestures that are not normally offered to strangers.

(Taken 7th May 2015, Lincoln High Street).

Audience

Our performance relied on audience participation and so learning about how to engage and interact with the public was extremely important. In Govan’s article, Between Routes and Roots, Dudley Cocke describes how the Roadside Company engages their audience by “sharing and celebrating local music, and narratives of place often provided the starting point for devising a performance” (Govan, 2007, 137) and how this successfully engages “local audiences in performance-making” (Govan, 2007, 137). Therefore, by giving the audience something they can relate to and understand, ultimately allows them to feel comfortable and more willing to participate in the performance. This is why the content on the signs were colloquial and recognisable. We wanted the audience to feel comfortable which is why we used gestures that they would have been able to recognise and render familiar.

I was inspired by the way Hannah Walker and Chris Thorpe involved their audience members in their performance of, I Wish I was Lonely. Their techniques provided me with ideas about how to engage our audience and this was important because we were dealing with possibly thousands of audience members and we needed to find a way to connect and interact with them. In Thorpe and Walker’s I Wish I Was Lonely performance, the performers involved the audience to the extent that the audience themselves were the performers. We were asked to keep our phones on and to answer any call we received. Dialogue between the performers would be interrupted and we were encouraged to answer the calls and act normal in order to have an authentic conversation. The performers informed us of the difficulties of interacting and including the audience members. They emphasised the importance of creating “a way out” (Thorpe and Walker, 2015) for audience members who were unwilling or unconfident in participating. The performers also informed us that the key aspect of audience interaction is to avoid making the audience members feel uncomfortable by “respecting their decisions” (Thorpe and Walker, 2015). The advice Thorpe and Walker gave to us influenced the way we interacted with the public during our performance. We respected our audience members by not forcing our presence upon them, instead we awaited their reactions and responded to them as much as they were responding to us.

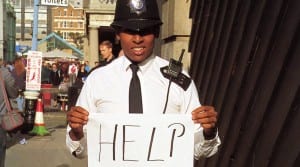

Another practitioner who inspired our work was Gillian Wearing who describes her work as “editing life” (Stonard, 2001). She documents the confessions of real people through photography and film. These people’s own personal thoughts are put on public display which creates a powerful visual spectacle.

Photo found here: http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/gillian-wearing/

This photo of the policeman holding the ‘help’ sign really stood out to me because it can be interpreted in different ways. Wearing’s work inspired me to think about ways to create something as bold and engaging. By using signs, we created visual spectacles that captured the public’s eye and caught their attention. The work we created was designed to liberate the public from consumerism in the high street by engaging and interacting with them. We wanted reactions from the public in order to give them some type of liberating release, like the policeman in Wearing’s photograph. Wearing liberates the people she encounters by allowing them the freedom of speech in a safe, inviting environment. Of course, not everyone is willing to be a part of something like this, but when someone does engage and open themselves up to possibility, they are liberating themselves from the constraints of modern society. This example of creativity and bravery inspired us to create our own work which defies social boundaries and liberates us and the public from social normalities and consumerism. Our signs were designed to disrupt the public’s set journeys and to give them the opportunity of distraction by interacting with us. Wearing creates a visual spectacle that has personal meaning which is something we wanted to incorporate into our piece which is why we chose the “What would you write?” sign. Like Wearing, we were able to give our audience the freedom of expression.

(Taken 7th May 2015, Lincoln High Street).

I also researched into Happenings because, like our performance, Happenings always place the audience at the centre of their performances. A Happening is a type of performance which is concerned with the message being received by the audience. “Today we think in terms of ‘messages sent and received’ and understand that perception is a relationship between the sender, the message, and the receiver” (Schechner, 1995, 216). We think this way because we are used to being surrounded by technology which commonly use this kind of terminology (emails, sms texts, social network sites). Our own performance was highly based around audience involvement and reaction, not only this but we wanted to receive the audience’s own personal responses to the piece. “Happenings leave to the audience […] the job of ‘putting something together’ or ‘making something out of’” (Schechner, 1995, 218). The audience is presented as the most important aspect of the performance because they are given the opportunity to be actively involved in creating and/or deciphering the performance, and this type of intimate involvement ultimately gives them the freedom to determine the outcome of the performance. The participants of Happening’s have been offered a kind of freedom and “the receiver now confronts the freedom which is difficult to avoid once presented, and equally risky to accept” (Schechner, 1995, 218). This statement highlights the lack of freedom the average person experiences and as a result, they yearn to feel a sense of freedom, even if it is merely to do something silly or different even for a fleeting moment. The desire for freedom is strong, however, the public sees this extent of freedom as a challenge against social boundaries, and so they are fearful of the consequences. “Happenings challenge theatre people to re-examine the stage […] focus and relationship to the audience” (Schechner, 1995, 218) On the stage, audience interaction is always set in a safe, controlled environment in contrast with the city in which the unexpected can happen and a certain feeling of safety is diminished. Chance occurrences and spontaneous events have the ability to change an entire performance which is why Happenings are based around audience experience and involvement. Taking this into consideration, I thought about the importance of audience interaction and the spontaneous events that may happen. Researching Happenings prepared me to expect the unexpected and to embrace chance occurrences if and when they were to happen.

Another practitioner who inspired our work was Antony Gormley who created an artistic, creative piece called One and Other in which he would invite members of the public to occupy the Fourth Plinth for one hour each, within 24 hours a day, for 100 days. Gormley takes the contextual aspect of Trafalgar Square and juxtaposes it against contemporary society in order to “reflect on the diversity, vulnerability and particularity of the individual” (Gormley, 2009). Like our performance, Gormley gives the public an opportunity of freedom and a sense of release. Gormley comments that his work is “about people coming together to do something extraordinary and unpredictable. It could be tragic but it could also be funny” (Gormley, 2009). Gormley includes the public and gives them the full power to perform how they please and like Happenings, the unpredictable outcome of the performance is what makes it spontaneous and authentic. Here is a photo of one member of the public who participated in One and Other:

Photo found here: http://www.antonygormley.com/uploads/images/uk_oneandother_2009_005_web.jpg

Reflecting Back: A Performance Evaluation.

The ‘March of the Guard’ particularly worked well because it contrasted the informal casual moments with the more formal moments. The formality of the ‘March of the Guard’ ritual emphasised the seriousness of our performance and highlighted the importance of human interaction.

(Taken 7th May 2015, Lincoln High Street).

During the performance, we interacted with a large number of the public and I was surprised at how great the reaction was. A lot of people seemed more than happy to approach and interact with me and many of them asked what I was doing and seemed genuinely interested. One young man especially seemed very enthusiastic, expressing how he thought what we were doing was ‘amazing’ and how he really wanted to write on our ‘What would you write?’ sign. I asked him, if he were to hold a sign, what would he have written on it and he chose to write ‘Can we dance?’. This was really amazing because after the young man left, I held the sign and received a lot of positive responses and more than three people danced with me in the rain.

(Taken 7th May 2015, Lincoln High Street).

Site specific has taught me that a performance can be held anywhere, not only on a stage and how the site itself allows the performers to make the space perform as much as the space makes them perform. I have also learnt that the contextual and historical aspect of the site shapes the performance itself and for Fiona Wilkie, “site specific performance engages with site as symbol, site as story-teller, site as structure” (Pearson, 2010, 8). Our performance reflected the current, contemporary use of the high street and judging by the amount of positive responses we received from the public, our performance was an overall success.

Word Count: 3,226.

Bibliography:

Debord, G. (1992) Society of the Spectacle and Other Films. London: Rebel Press.

Elster, J. (eds.) (1986) Karl Marx: A Reader. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Foust, C. and Jones, R. (2008) Staging and Enforcing Consumerism in the City: The Performance of Othering on the 16th Street Mall. Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, 4 (1) 1-28.

Freud, S. (1997) The Interpretation of Dreams. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Edition Limited.

Gormley, A. One and Other, Fourth Plinth Commission, Trafalgar Square, London, 2009. [online] Available from: http://www.antonygormley.com/show/item-view/id/2277 [Accessed 24 April 2015].

Govan, (2007). Between Routes and Roots. Performance, Place and Diaspora. 136-143.

Pearson, M. (2010) Site Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Plant, S. (1992) The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age. London: Routledge.

Stonard, J. (2001) Gillian Wearing OBE. [online] New York: Tate. Available from: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/gillian-wearing-obe-2648 [Accessed 25 February 2015].

Schechner, R. (1995) Happenings. In Sandford, M. (ed.) Happenings and Other Acts. London: Routledge, 216-218.

Walker, H. J. and Thorpe, C. (2015) I Wish I Was Lonely. [performance] Hannah Jane Walker and Chris Thorpe (dir.) Lincoln: Lincoln Performing Arts Centre, 11 February.