Liberation Rituals – Framing Statement

Heavily influenced by performance art practitioners Marina Abramovic and Rebecca Twydell my piece, Eight Liberation Rituals, inhabits the idea of offering myself as an object of psychological experimentation to audiences. Incorporating themes found in Abramovic’s The Artist is Present (Abramovic, 2012) I have created an exploration into liberating from a state of acute anguish, loss and bereavement. Using theoretical insights into the relationship of site and performance developed by Mike Pearson, I have transformed a space with great personal resonance into an expressive piece of performance art.

My piece is centred on the loss of my dad, who passed away suddenly in late 2014. I was in Lincoln, travelling from my home to the high street when I received the news of his death. I was located under a passage way that connects the waterfront to the high-street. Ever since, I have avoided that same passage when travelling to the high-street – I divert, taking a longer route in fear of the emotions that may overwhelm me. This is the space my piece targets.

After exploring other Site-Specific work, such as Sit with me for a moment and remember (Pinchbeck, 2012) inspired me with an initial idea that I can transport an audience from two contrasting places, that I could transform this space from a place of pain and grief to a place of beauty, freedom and acceptance. With this in mind, I began to link this transformation with our brief of liberty and freedom. Developing my first idea, I started to research into site-specific performance related to transformation, this is when Rebecca Twydell’s piece, Re–generation Spells, (Twydell, 2010) became a big influence to my work. Like her, I could physically transform the tunnel to a much brighter, cleaner place by using a number of rituals.

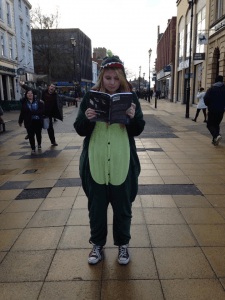

I have devised eight rituals in order to cleanse the space from its sadness. They have been recorded for the purpose of my performance instillation. On the 8th of May 2015 eight spectators, whom have been invited prior to the event, are encouraged to visit a screening located in a studio, sitting silently across from the performer for duration of their choosing, becoming participants in the performance.

By researching into this particular space, I gained a clearer understanding of what Site-Specific performance is. In addition to exploring a space because of what I find interesting about it, it is also important to research into the historical background of a place. To fully appreciate the place in an existing life, I needed to figure out its past. Marvin Carlson suggests that “places of public performance … are marked by the traces of their other purposes and haunted by the ghosts of those who have used them in the past” (Govan, 2007, 139). By discovering the original ‘roots’ of a place, we are able to imagine the place as it once stood and in doing so, we have the advantage of re-creating or re-experiencing the past and merging it with the present.

Knowing that this site was used by the Romans as a central trading market for boats and that it’s the oldest standing bridge that still has buildings on top of it dating back to 1160 A.D made me engage in the variety of what a location means to diverse people, the many contexts the space can be portrayed – the journeys, not just physically but emotionally and mentally too, ‘Layers of the site are revealed through reference to historical documentation, site usage (past/present), sound, personal associations, half-truths and lies.’ (Wilkie, 2002a, 150, as cited in Pearson, 2010, 8) Taking this into consideration I now understand that everyone has diverse opinions when observing this space, most just see it as a walkway, some will have a more personal connection but more specifically the way I perceive the place in a unique way and how my experience of the tunnel is now a part of its life-long history.

(The Glory Hole, Lincoln, 2001)

Exploration:

In the early stages of exploration, I followed a number of Pearson’s strategies in hope to find a space which I felt connected to. One practice that lead me to the subject of piece was Field Working (Pearson, 2010). Pearson created his own methods for making theatre in a variety of contexts and locations, including Field working; Field walking. This was a key exploration exercise for innovating ideas for my own piece. This exercise involves revisiting the same location but on diverse days, times and weather conditions; noting down all the changes in nature in hope to create a personal response.

Similar to this, Tim Etchell, a practitioner who focuses on performance and site devising a piece which focuses on the change in site. In ‘Exploration’ the notion of attentiveness and observation is highlighted. The term, “dead of night” (Etchell, 1999, 76) suggests that darkness prevents investigation of a space because it shrouds the places around us and restricts our sight. In the morning, however, the light enables us to explore because it gives us a sense of security. Harbisson describes this “veiled arrival” (Etchell, 1999, 76) as “acting out an allegory of knowledge” (Etchell, 1999, 76). I decided to take upon his theory and visit my site once in the morning and once a night to see if the physical appearance of the space was actually camouflaged by light and also to see how my emotions would change about the tunnel in the diverse conditions. Interestingly, I felt less fearful of the space at night – it’s true that I couldn’t see the full extent of the walkway whereas in the morning I felt more discomfort as I could see all of its scars, the graffiti, cobwebs and just the general abandoned ness of the place. Alongside this, I also felt more negative emotions to the space during the morning as I visited the tunnel at approximately 8.30am the same time I had the phone call to say my father had passed away. From gathering this information I felt that if I was going to produce work that was authentic and therefor the most painful I should avoid working with the space at nigh time so it couldn’t hide away my emotions.

(March 23rd 2015, The Tunnel in the day)

Another piece of Etchell’s that greatly inspired me for my own work was ‘Maintenance’ – a piece which demonstrates one performer’s continuous “ritual” (Etchell, 1999, 77). The performer walks the same journey at the same time every day for a period of a. Part of the piece includes bizarre rituals, behaviour that is not normally accepted in an urban environment. The performers unique actions opposes to the everyday normalities of life but the man’s repetitive nature can reflect a human’s tendency to repeat their everyday routine as if it is ritualistic, for example getting up, going to work and going to bed. This influenced me when devising my own rituals, the majority only use the tunnel when travelling to and from the high street, therefore I thought, alike ‘Maintenance’ that it would be an effective introduction to my rituals if I was to simply walk through the tunnel – mirroring its everyday use but with an underlying meaning of confronting the tunnel before creating more personal rituals.

Besides Etchells, another practitioner who inspired me in the creating process of my piece was Larvey and his instruction of ‘Making the public, private’. This specific instruction influenced me to show the full extent of my personal discomfort by confront the tunnel and therefore produce a piece that shows this. ‘The urge to show everything come what may…turns the theatre into mere illustration of the author’s words’ (Pitches, 2003, 49) Adhering to the general rules of Site-Specific performance I decided that It would be effective to bring the public to the location of the performance, however after a lot of consideration the tunnel is a main link to the high-street and with it being so narrow I would be making an obstruction to the public who do not wish to participate in the performance. Due to this I had to make a solution that would avoid blocking off the busy traffic but still performing in the space – this lead me onto the idea of recording a piece at the space and then screening it later to an audience which would relate to another key theme of our brief, pervasive media.

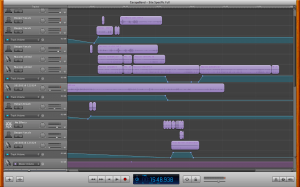

I started to research into performances that involved recording, one particular site-specific performance was Super Night Shot, produced by touring performing group Gob Squad. The group take the streets of Leicester in a split screen video experience filmed an hour before audiences arrive, Super Night Shot contains no cuts or edits and is produced with four synchronised video cameras by four performers. ‘Performers declare a “War on Anonymity” before taking to the city streets on a set of magical adventures that celebrate unplanned meetings with strangers’ in a military style format. This inspired me to use little edits in my own video in order to represent an authentic performance.

(Super Night Shot, Gob Squad, 2014)

Devising process:

However I still had no content to my work? What will I be doing on this recording? Will it have literal meaning or more of a metaphorical meaning? After discussing with my teacher about these questions he guided me towards a previous student, Rebecca Twydell, piece ‘Re–generation spells’ where audience members were invited to act upon rituals she had formulated. With already knowing that audience participation wouldn’t be possible and despite the context of Twydell’s piece being unlike my own, the general idea that she uses rituals to transmute a space seemed stimulating. Could I create my own rituals, could they cleanse the space of the negative connotations I portray it with?

I started to create themes of cleanse to create my set of rituals with. I decided that due to the nature of the piece each of the rituals should be compelling for me – liberating me from the fear and bereavement felt when entering the space. As already stated, after the loss I found it difficult to revisit the site therefore I felt my first ritual should be aimed to conquer this anxiety would be to simply travel through the tunnel, ‘walk the tunnel, feel the coldness on your feet’. My second ritual challenged the first, in order to see a different light in the tunnel I needed to see it differently – therefore my second ritual ‘walk the tunnel again, but this time use a blindfold,’ was to walk through the tunnel blindfolded to see how this changed my perception of the tunnel, if I could map the space differently. Following this, taking on board the cleansing idea I literally wanted to clean the tunnel from its graffiti and other traces of recklessness. My third ritual, ‘wash the wall and then wash it again’ I decided that due to time constraints it would not be possible for me to clean the whole of the tunnel and instead I would just pick a small part to clean thoroughly and with the care that it deserves. I decided that an hour would be an appropriate time for this. The next ritual I devised was again following the cleansing idea. Ritual four ‘Sweep the tunnel and then sweep again’ consisted of sweeping the same spot of the tunnel for an hour. I decided – knowing I would now have to perform in the studio I could collate the traces of dirt and grime and bottle it up to showcase it in the screening. My next ritual I wanted to just be present in the space to see if again I felt differently about it after the cleanse, my fifth ritual was to ‘lie down and just be present in the tunnel’ was a moment I could then reflect on my feelings towards the space and my dad. The next ritual ‘Decorate the tunnel, make it something of beauty’, after not receiving permission to physically dress the tunnel I decided to use a projection of my dad to make it something of beauty. I projected a picture on the spot I cleaned, I chose a picture of him on the last holiday we went on in order to bring memories of happiness to the tunnel. The seventh ritual ‘Write a letter to the tunnel, and let it burn’ I wanted to write all the negative things about my loss and destroy them – liberating me from them. My final ritual ‘Leave the space’ was to simply walk away from the tunnel and leave behind the memories of transformation in hope that when I revisit the space, I will fell a lot differently.

Although I had already started to feel the psychological effects of actively thinking about the loss of my dad I was not prepared for the emotions felt when actually doing the rituals. I spread the doing of rituals over two days – again early morning, similar to the time I heard about the news. I invited somebody I trusted dearly, who recorded the whole journey.

(27th of March/3rd of April 2015 – pictures from the day I did the rituals)

Previous to the doing of rituals, I came across an article about Marina Abramovic, and how she prepared for her most recent performance The Artist is Present. She described the process by ‘Sitting straight and allowing my breath to crinkle out memories, thoughts, and emotional treasures were enjoyable in a way, and although I could have physically continued on, in an instant, I felt my heart curl inwards and I knew that the growing and opening had come to a close for the day. My emotional self was exhausted’ (Abramovic, 2012) Similar to Abramovic, I am too pushing myself mentally, to limits I find uncomfortable by actively thinking about my loss for the purpose of my piece. Abramovic designed her own exercises and regimes in order to prepare herself and her performers for their shows, one performer from The Artist is Present, described the rehearsal process as ‘a challenge, but a blessing in disguise’ as she had to change so many factors about her body, ‘Because of the show, everything in my life changed; my diet, my body, the depth of my sleep, my energy levels, the depth of my breath and most importantly my respect for my own limits and an eagerness to overthrow those limits each day’ (Bailey, 2010) This training instilled impeccable mental and physical strength in her students, something I could merely admire rather than practise due to time constraints. Abramovic was a major influence in helping me on the day of my rituals, although I felt exhausted and emotional the outcome drove me to finish them.

(The Artist is Present, Marina Abramovic, 2012)

After finding the rehearsal process of the Artist is Present so inspirational, I decided to look into more of Abramovic’s work. I came across Seven Easy Pieces, which was a montage of performances focussing on the theme of liberty and Oppression. The seven works were performed for seven hours each, over the course of seven consecutive days, and more specifically the sixth piece of the seven, Lips of Thomas (Abramovic, 1975) was a piece devised from rituals. Despite Abramovic’s intensely preparing for her other works, she only planned these performances rather than rehearsed them, this way she had no control of how she would react to the actions themselves creating a totally authentic piece. Part of the performance consisted of repeatedly whipping herself for a long period of time, although marina persisted to quiver and that spectators were saying, “Please, please stop,” or “You do not have to do it more” (Brockes, 2014) again and again, Marina continued. However, Abramovic did not quit the performance. This inspired me, as although I had pre-recorded the video, and I have somewhat scripted an experimental piece I still, due to the sensitivity of the subject matter, will have no control over my emotions on the day.

(Lips of Thomas, Marina Abramovic, 1975)

Now having recorded all of the rituals, I decided, like Abramovic I should too perform live at the screening, creating a more authentic piece. I had already decided that I wanted to showcase the tools I had use to cleanse the space, including the dress I wore on the day as they were key pieces valuable to the storytelling of the piece. I decided that I should be present at the screening to aid the clarity of the piece. I thought it would be effective if I repeated the process of cleansing but using the dirty water and filth found at the site when cleaning, onto the dress. I will then at the end of the performance be wearing the filthy dress. This symbolises that although I have cleansed the space and; in the performance done the act of cleaning the dress, in hope to feel liberated from the negative emotions at the site, I will never be completely free from the sadness and I will always wear the pain and hurt felt from my loss. Additionally, I feel that transforming the white dress to one that is dirty and therefore somewhat black in colour, would symbolise funeral attire – suggesting there is some acceptance of the site and my dad’s loss after doing the rituals. In addition, I devised a script explaining why and how I did the rituals which was spoken in between each ritual.

Final Performance:

During the performance, I wanted to create an intimate experience in which I allowed the audience to be very close to me. Some parts of the video were silent; this allowed the ambient sound of the dripping of the water and the scrapping of the brush when cleansing become very effective adding to the intense atmosphere of the piece.

In reflection, although I am very proud of the piece I produced, there are many improvements I would make if I was to recreate the performance again. Although I believe the studio experience was effective, I still debate whether the performance would have been more effective if I performed there at the site; however this would have took much organisation in order to get permission to possible close off or use this space, something time constraints didn’t allow me to do. In addition to this, I would have liked to incorporate more understanding of the rituals I did on the day into the live performance, I question now if audiences understood what I was doing with the objects as a live performer? I also would have liked to have further studied into Abramovic and followed some of her rehearsal methods in more depth in order to prepare me as a better performer. Finally, I only invited eight people, those of which were friends of mine and those who already knew my circumstances, If I could reproduce this piece, I would find it interesting to see reactions of those who do not know me and those who are strangers to the site. Despite this, I feel my performance was authentic, using the rituals and the whole process of Site-Specific performance; I had achieved my performance intention – to cleanse the space from its negative connotations and therefore be able to return to the space. I also feel I achieved an effective performance that showcased the tunnel of some part of its history, I used the site to symbolise my grieving process, tell my experience of the space and produce an expressive piece of art, adhering to Pearson’s theory, “Site as symbol, site as story-teller, site as structure” (Pearson, 2010, 8).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z5r5jFjGwKo&feature=youtu.be

(Liberation Rituals, 2015, Final cut of video performance)

Words: 3,251

Bibliography:

Abramovic, M. (1975) Lips of Thomas [Performance] Marina Abramovic (dir)

Abramovic, M. (2012) The Artist is Present [Performance] Marina Abramociv (dir)

Brittany Bailey. (2010). PREPARING FOR PERFORMANCE ART WITH MARINA ABRAMOVIC. Available: http://gnomemag.com/preparing-for-performance-art-with-marina-abramovic/. Last accessed 4 May 2015.

Emma Brockes. (2014). Have you got what it takes to do the Abramovic method?. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/12/marina-abramovic-ready-to-die-serpentine-gallery-512-hours. Last accessed 4 May 2015.

Etchell, T. (1999) Certain Fragments. Eight Fragments on Theatre and City. London: Routledge.

Gob Squad (2006) Super Night Shot. [performance] Gob Squad. Leicester: Comedy Festival, February.

Govan, (2007). Between Routes and Roots. Performance, Place and Diaspora. 136-143.

Laverly, C. (2005) 25 Instructions for Performance in Cities. Teaching Performance Studies, 25(3)229-238.

Pinckbeck, M. (2012) Sit With Me for a Moment and Remember. [Performance] Michael Pinckbeck (dir.) .

Twydell, R. (2010) Re-generation Spells [Performance] Rebecca Twydell (dir)

Mike, P. (2010) Site-specific performance. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.