Site Specific Final Blog Post

Framing Statement

As part of our Site Specific module for University we were asked to create a Site Specific performance exploring the idea of pervasive media. For this task I was in a group with Rachel Mudd and Kerry McCarthy. We were given the choice of two locations, the Brayford Pool and Lincoln High Street and asked to explore the idea of liberty. We selected to look at the Brayford, mainly for its connections to water and the free-flowing connotations associated with it. The final performance piece was to be an audio experience which would include live elements. Due to these live elements, audience numbers were restricted. Each individual experience would last 20 minutes with the headphones and audio device provided.

Fundamentally, site specific is a performance that was ‘conceived on the basis of a place in the real world’ (Pearson, 2010, 7). The space itself helps create the piece and is ‘not an empty container but an active agent; it shapes what goes on within it’ (McAuley, 2000, 40). As such it is crucial to understand the intricate details of the history of your location. For our piece we chose to combine the history of the Brayford with the elemental basics of water itself in order to contextualise our piece on a wider scale.

To further our understanding of our task we explored previous performances that had included an element of pervasive media. Some of our main influences included the mobile phone based performance I Wish I Was Lonely (Walker and Thorpe, 2015) and the reflective audio experience Sit With Me for a Moment and Remember (Pinckbeck, 2012). These helped us understand the role pervasive media can play within a performance context; additionally using The Pervasive Media Cookbook (2012) to reinforce how to ‘interleave media content with our real world awareness of our bodies in space and time’ (The Pervasive Media Cookbook, 2012). This combination of media and visual elements as well as physical components was something we were interested in exploring with our final performance.

Having gained a grasp on the task set out for us we researched the Brayford itself. In order to do this we looked through both the University and the local city library to delve into the history of the site. This allowed us access to an understanding of the vital composition of our site. It also encouraged us to go and look at the Brayford from another perspective and try to imagine what it might have looked like in the past. This visualisation of the history gave us a clearer picture of the aspects we wanted to portray in our final performance.

Throughout the process we knew that we wanted the audience to actively participate in the final piece. We felt that this would allow for a more personal voyage of discovery which would resonate with them for longer than a simply observational piece would. We also felt it was important for us to be present as a possible physical connection to the voice in their ear and also so that we could act as markers for their next location on tour.

Analysis of the Process

Technological Introductions

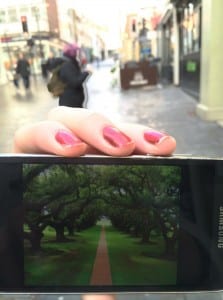

Before settling on the idea of an audio experience, my group investigated various ways of producing a performance through technology. We experimented with contrasting the cold-concrete of cities with the peaceful greenery of the countryside by creating ‘a forest in the city’ (Laverly, 2005, 286). We did this by simply holding an image of a forest up against the backdrop of the busy high-street to create an entirely new image.

Site-specific performances invite the audience to become ‘the creative pedestrian as the new architect of the city’ (Wrights and Sites, 2008); allowing them to reinvent the way they see locations. Though this experiment helped us understand the motivations behind site-based performances; it was not sufficient to create a final performance piece from so we looked elsewhere for more ideas.

We ended up seeing a video of Gob Squads Super Night Shot (2006). This inspired us to investigate the use of video to create a performance. Using the idea of timed intervals we visited the Brayford at various time points throughout the day, documenting each with a ten minute video. Superimposing a real-time video of our feet walking down the Brayford on top, we time-lapsed each of the videos in order to create a short three-minute performance. We ended the video with a simple black frame around the text ‘The events just witnessed will never be seen again'(Naomi Jones, 2015). Our idea behind this was to get the audience to consider the passing of time and make them think about the finer details of life that are missed through the focus on technology. However, feedback showed that the sped up variations of the videos caused events to become blurry, stopping people from noticing anything in finer detail. After this we looked for a way that would open the audience’s eyes to the world around them more, giving them time to consider what the Brayford represents for them.

Timelapse on the Brayford Wharf

Listening for an Answer

From this point we explored the idea of creating an audio experience using Our Broken Voice (Circumstance, 2010) as a main source of inspiration. Their idea of a subtlemob was fascinating; a ‘subtlemob is an invisible flashmob, it integrates with the beauty of the everyday world’ (Circumstance, 2010). The idea that there is only one audience member but numerous oblivious performers inspired us to explore in greater detail the relationship between a performer and their audience.

Technology provides us with greater flexibility for proximity, meaning that “sites today can therefore be virtual, and group events can take place remotely” (Ferdman, 2013, 7). The new forms of interaction mean that there is no longer a requirement for the performer to be present resulting in liberation from traditional performance practices.

Despite this, we were intrigued by the connection between performer and audience in Pinchbeck’s Sit With Me For a Moment and Remember (2012). The presence of a silent performer, we felt added a personal touch to the performance, giving the audience a more intimate connection to the voice they were listening to. Using this idea we decided to have three ‘moments’ throughout, one at each of the locations visited during the experience. The locations were at either end of the Brayford and in the middle. We chose these specifically to ensure that the audience were able to perceive the Brayford in a different way both physically and metaphorically.

Exploring the Depths of the Brayford

‘Site determines not only the location we find ourselves in but also its construction, its historical legacies’ (Ferdman, 2013, 13).

Using this idea that “The city is, rather than a state of mind, a body of customs and traditions” (Hahn ,2014, 31), we realised that in order to fully submerge ourselves in the atmosphere of the Brayford, we would have to understand its history. To do this we visited the Central library. This was useful in providing detailed information about buildings that had once been central to life in Lincoln. This allowed my group to gain a breadth of knowledge about the history of the Brayford that we could discuss as part of our audio tour. One aspect of information I found particularly interesting was the transcriptions of the Council’s previous plans for the Brayford as well as discussions on its state at the time the books were being written. One report noted that “Commercial use of the Pool has dwindled over the years and leisure boating has taken over”(Laidler, 1989). I found this particularly poignant considering the recent commercial renovation of the Brayford, its edges now lined with restaurants and hotels from which we hoped to distract the audience’s attention. However, this statement did act as a stark reminder of the speed in which things change and develop in as short a period of time as thirty years. We used much of our findings as script so that the audience felt as though they were ‘hearing the ‘voices’ of the history of a place’(Pervasive Media Cookbook, 2012), allowing them to feel a more personal connection to the past.

In order to create a performance that was grounded in the current day Brayford yet honoured the past, we visited Lincoln Museum. This helped us ‘in creating a present that is itself multitemporal’ (Pearson, 2010, 42). Being able to physically see remnants of the past gave us a clearer picture of how to transpose this into a descriptive, vivid picture for our audience.

With water being central to our performance, it meant the specifics of our site were in a constant state of movement, ever changing and flowing. This gave us a great level of freedom with our site, enabling us to contextualise it in a geographical sense through the interconnectivity of water, the constant flow of water reflecting the idea that ‘mobility is coded as freedom’ (Wilkie, 2012, 206). This interconnectivity ironically links with the technology from which we wanted to distract our audience. The show I Wish I Was Lonely (Walker and Thorpe, 2015) posed a similar dilemma, in that technology was used both as a liberation and justification for devotion to technology. It demonstrated ways that technology can turn a ‘city into a sonic space open to peripatetic exploration’ (Hahn, 2014, 29). The show was useful when considering ‘the isolation of individuals inherent in this social spectacle’ (Govan, 2007,140).

Due to this we had to ensure our performance was grounded, to the extent that ‘aspects of the location become integral to the overall form and content’ (Couillard, 2006, 32). This is where the historical research was most helpful, as every place has its own unique past.

The Fluidity of Language

We knew from the start that we wanted some form of interaction between the performer and the audience. Our initial thought was to use paper boats; we decided that at the end of the piece we wanted the audience to place their own paper boat into the water as their personal contribution to the history of the site. Originally we toyed with the idea of water-soluble paper; however the speed with which this dissolution occurred did not leave enough time for the audience member to dwell on the moment.

Originally we struggled with content, not wishing to make the piece a purely factual, historical tour like Ports of Call (University of East London, 2008). Though they were helpful when considering the language of water and using the voices of history to tell the story; this caused us to realise the problem of how to mix the detailed history and the liberation of water into a twenty-minute performance.

We initially struggled with this, but once we had spoken to Colonel Ron Dadswell OBE and interviewed him about his time in the North Sea (Mudd, 2015), directly connected to the Brayford, we found the content easier to structure.

Whilst developing the script we were inspired to delve deeper into the University itself and its relationship with the Brayford. Upon further investigation we found that the Brayford plays a prominent role in the University Coat of Arms. The two swans representing strength, self-confidence and loyalty and the “reversed pall is a representation of rivers and canals” (University of Lincoln, 2011). Though perhaps the most significant discovery was that of the meaning behind the University motto; ‘Libertas per Sapientiam´ which means ‘Through Wisdom, Liberty’ (University of Lincoln, 2011).

This concept of wisdom resulting in freedom is especially compelling when considering our own project’s theme of liberation. Our focus has primarily been on the freedom of water and the interconnectedness it causes, largely inspired by the Heraclitus quote “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for he is not the same man, and it’s not the same river” (Good Reads, 2015). The idea that water is constantly changing and has the ability to take us almost anywhere in the world is a truly liberating concept. This brought me to think about the freedom of the site specific performance itself, liberated from the constraints of a traditional theatre.

We went through many variations of scripts before settling on a condensed version which we were then able to record. We tried to incorporate phrases such as ‘dead ahead’ (Nautical Know How, 2015). We felt that this would help the audience position themselves more ‘on the boundary between private and public spheres’ (Tapper, 2014,150), society whirling on around them, whilst they take a private voyage of discovery down the Brayford.

Listening to Water

The recording process itself brought up its own range of challenges. Using Carrlands (The Carrlands Project, 2007) as an original guideline for appropriate tone of voice, we experimented with various ways of recording our script. One of the first problems we faced was an audible burst or air sounding when speaking plosive letters such as ‘p’ and ‘b’. We discovered that adjusting the angling of the microphone got rid of this problem.

Having experimented with different ways of recording our own voices we then explored different ways of incorporating water sound effects to create added layer onto the piece. We recorded water from various locations including the River Humber and a weir from a canal at my hometown:

Ultimately we found that none of these recordings were appropriate as the water was not distinct enough from white noise. This resulted in us using a recording from the North Sea found online from Soundcloud(2015):

Another problem we faced when recording our audio piece was white noise. White noise is inevitable when working in anything but a professional studio. White noise ‘is a special type of random noise where the energy content is the same at each frequency’(Yun, 2014, 49; this makes it incredibly difficult to edit out and we experimented with different ways of cancelling it out throughout the development process.

Going Against the Flow

Our first trial run on the Brayford was conducted with ourselves as the audience. Although this meant that we lacked the live elements of the performance it gave us the opportunity to test the practicality of the recording. We found that our initial timings for walking between locations had been overestimated, allowing three minutes more than necessary to walk to the final location. This was something of a relief as the initial recording had lasted well over twenty-five minutes.

We also discovered that our instructions for the audience member on travelling between locations were too rushed and did not give the participant enough of a chance to register the information before more was added on. To rectify this in our next version, we examined the script for A Hackney 4th July (Hunter and Lawrence, 2009), specifically looking at the language that was used to directly address the audience. Although this was performed in person rather than through an audio device, a similar premise stands. Simple yet poetic instructions such as ‘turn right at the front door and Hoxton Street is our Atlantic, where we’ll carry ourselves to the water’ (Hunter and Lawrence, 2009), were useful in understanding how to be clear with our objectives whist maintaining the flow of the text. These also helped make the piece more relaxed, and less of a formal lecture so creating a friendlier voice that the audience could connect to.

Another problem we faced was volume as we realised that our own recorded pieces were far too quiet whereas the samples of the phone call with Ron were booming with volume, making listening uncomfortable for the listener:

The final glitch in our trial was watching our paper boat being placed in the water only for it to end up trapped in a pile of rubbish.

Performance Evaluation – Going Against the Flow for a Final Time

With dark clouds dangerously looming above us we tentatively set out to complete our final performance. Thankfully the heavens remained closed until the final audience member departed. The weather did somewhat affect this version of our performance though being an outside location, the climate ‘will doubtless impact upon site-specific performance’ (Pearson, 2010, 102). We had been aware of this being a possibility so to ensure that we as performers remained dry we all wore matching rain macs.

Matching outfits also worked well as a uniform that distinguished performers from the members of the public. We were able to act as beacons, making it more obvious for the audience to know where to go next; this worked successfully.

Through previous runs we had calculated an appropriate amount of time to walk between locations. Although we would never be able to be 100% accurate with the time in which the audience would arrive at each location due to extraneous factors such as walking speed and crowding, I believe that we left enough time for both practicalities and contemplative periods.

Equalising the volume of multiple voices proved to be a problem as it had previously. Through various editing techniques, we eventually managed to even these out:

However, our decision to use high quality audio and listening devices was both a blessing and a curse. Though they provided a professional level of audio, any editing problems were immediately recognisable. For example there was some level of fuzziness in the voice recordings that we could not eliminate without a proper sound-proofed studio and more advanced editing equipment.

Overall I feel that the final performance went well. The placing of colourful paper boats along the start section of the Brayford added some colour into an otherwise dull day. It also allowed members of the public who were not participating in the audio part of the experience to be distracted from the everyday, even if just for a few seconds.

Though we only had six audience members the response seemed to be positive. All followed the instructions correctly to end up at the right area of the Brayford at each point. However, if we were to do this again I would create a more distinct start location. Though it was obvious by the end of the day through the presence of the paper boats, it could have been more clear from the outset.

Overall this process has exposed/introduced me to performances that do not fit with what is usually perceived as theatre. Developing the piece, looking into the historical detail, examining our location in intricate detail, helped me engage more with Wilkie’s conception ‘“site as symbol, site as story-teller, site as structure”’ (Pearson, 2010, 8). It has opened my eyes to Ubersfeld’s idea that performances do not need to just take place in a conventional theatre as fundamentally; ‘Theatre is space’ (McAuley, 2000, 1).

Word Count: 3,187

Bibliography

The Carrlands Project (2007) Carrlands. [online] Cardiff Bay: Namesco. Available from http://www.carrlands.org.uk/ [Accessed 1 May 2015].

Circumstance (2010) Our Broken Voice. [performance] Circumstance. London.

Couillard, P. (2006) Site Responsive. Canadian Theatre Review, 126, 32-37.

Ferdman, B. (2013) A New Journey Through Other Spaces: Contemporary Performance Beyond “Site Specific”. Theatre, 43(2) 5-25.

Gob Squad (2006) Super Night Shot. [performance] Gob Squad. Leicester: Comedy Festival, February.

Good Reads (2015) Good Reads: Heraclitus: Quotes. [online] Available from http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/77989.Heraclitus [Accessed 28 March 2015].

Govan , (2007). ‘Between Routes and Roots’. In: Routledge (ed), Making a performance. 1st ed. England: Non.

Hahn, D. (2014) Performing Public Spaces, Staging Collective Memory. TDR: The Drama Review, 58 (3) 27-38.

Hunter, M. and Lawrence, C. (2009)A Hackney 4th of July. London: Hoxton Hall.

Laidler, K.J. (1989) Brayford Wharf North: Opportunities for Development. Lincoln.

Laverly, C. (2005) 25 Instructions for Performance in Cities. Teaching Performance Studies, 25(3)229-238.

McAuley, G. (2000) Space in Performance. United States of America: University of Michigan Press.

Mudd, R. (2015) Against The Flow Interview [telephone call] Conversation with Ron Dadswell, 17 March.

Naomi Jones (2015) Timelapse on the Brayford Wharf. [online] Available fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQe_SdL5KfQ&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 13 May 2015].

Nautical Know How (2015) Boating Basics Glossary of Terms. [online] Available from http://www.boatsafe.com/nauticalknowhow/gloss.htm [Accessed 11 May 2015].

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pinckbeck, M. (2012) Sit With Me for a Moment and Remember. [Performance] Michael Pinckbeck (dir.) .

The Pervasive Media Cookbook (2012) The Pervasive Media Cookbook. [online] Bristol: Pervasive Media Studio. Available from http://pervasivemediacookbook.com/essentials/experience/ [Accessed 1 May 2015].

Soundcloud (2015) Soundcloud. [online] Available fromhttp://freesound.org/search/?q=north+sea [Accessed 13 May 2015].

Tupper, J. (2014) Pervasive Games: Representations of Existential In-Between-Ness. Themes in Theatre: Collective Approaches to Theatre & Performance, 8, 143-160.

University of East London (2008) Ports of Call: Walks of Art at the Royal Docks. [online] London: University of East London. Available From http://www.portsofcall.org.uk/legal.html [Accessed 1st March 2015].

University of Lincoln (2011) University of Lincoln Coat of Arms. [online] Lincoln: University of Lincoln. Available from http://www.lincoln.ac.uk/home/abouttheuniversity/press/identity/coatofarms/ [Accessed 23 March 2015].

Walker, H.J. and Thorpe, C. (2015) I Wish I Was Lonely [performance] Lincoln: Lincoln Performing Arts Centre, 11 February.

Wilkie, F. (2012) Site-Specific Performance and the Mobility Turn. Contemporary Theatre Review, 22(2) 203-212.

Wrights and Sites (2008) A Manifesto for a New Walking Culture: ‘dealing with the city’. [online] Available From www.mis-guide.com/ws/documents/dealing.html [Accessed 09/04/2015].

Yun, Y. (2014) Noise Reduction & Gate Plug-ins in Audio Mixing Process. International Journal of Multimedia & Ubiquitous Engineering, 9(1)49-56.