Initially understanding Site Specific proved to be difficult. As a result I derived that it was any kind of performance that was particular to the site it was performed at. However, this assumption has changed and developed over the process of creating Collision. The sounds gathered are from a specific place, however, ‘there is no place of origin: a place owes its character not only the experiences it affords as sights, sounds etc. but also to what is done there as looking, listening, moving. Both ‘being’ and environment are mutually emergent, continuously brought into existence together.” (Pearson, 2010, 16) If we went back to the place they were recorded and tried to re-create them, they wouldn’t be the same because the time, the place and the people are all different. Despite this, it can be interesting to see what happens when the sounds are captured and moved to a different location.

What is Collision?

Collision is an audio experience created using original sounds captured on the High Street of Lincoln City Centre. Every sound heard was recorded on an iPhone, using Audacity to manipulate and create a different version of Lincoln. It is a sound experience that will stretch an audiences pre-existing notions of Lincoln by changing the sounds they hear everyday. Despite the manipulation, majority of the sounds are slightly recognisable yet different from what they have heard before.

Collision was performed in a blacked-out studio in Lincoln Performing Arts Centre on Friday 8th May. It is 16 minutes in duration per audience member with only one audience member at a time. In particular, the audience were asked the following questions in order to help to direct their thought process and liberate them from what they already view the city as:

What happens when you take sounds and put them in a new environment?

What happens when you collide the city with technology?

What happens when you sit in a room that is and isn’t there?

Pervasive Media

In order to use pervasive media we needed to understand exactly what Pervasive Media is. Pervasive Media Studio defines it as: “Digital Media delivered into the fabric of real life and based on the situational context at the moment of delivery.” (Pervasive Media Studio, 2015)

It can be also used for the public to play performance games. Pervasive games are a state of ‘in-between-ness’, “a space in-between real life, play, and discourse.” (Tapper, 2014, 145) this form of gaming creates “a double-identity, two aspects, which are both essential: first the existential in-between-ness, and secondly play as a contract” (Tapper, 2014, 156). To someone who is playing the pervasive game everybody who they encounter becomes another potential gamer. Tapper describes the encounter of a game player and someone who is not as ‘in-between-ness’. This space in-between play and reality is structurally embedded into pervasive games.” (Tapper, 2014, 150) The space in between ‘what is real’ and ‘what is not’ is an interesting place that can be explored further with Collision.

Performing in a City

Performing in a city can be a hard thing to start as “work can be made out of anything: there is no need for an audience or stage: and sometimes the performance will only exist through it’s documentation” (Lavery, 2005, 231). However, Lavery goes on to give 25 different ways of performing in the city. Maddie and myself decided to try number 25: “Interview people in the street about their dreams. Use this information to transform the city into a dream space” (Lavery, 2005, 236). After interviewing a few people we realised that this would be more difficult then we expected. Dreams have an aspect to them that feels real, yet things happen which would not happen in real life. However, we used this thought to create something out of the ordinary; by looking out of place yet doing ordinary things. In this way we managed to re-create a dream and see the results and reactions from the audience on the High Street.

By dressing up we saw a range of mixed reactions from the public of angry, confused and happy. Surprisingly, more people interacted then if I was dressed normally and people approached me rather than me approaching them. Buying coffee dressed as a dinosaur urged a little child to approach and ask my name in which case I found myself creating a character for the little child. What started off as recreating a dream, turned into creating a story from the story “postmodernists call this intertextuality: creating stories from stories, becoming a bricoleur of forms an organizer of materials” (Lavery, 2005, 230). This lead myself and Maddie to think of creating a dream landscape on the High Street whether we create for a specific audience member or as an installation. This also made us think as to how an audience might react and whether they would engage well with what we had created.

Etchell’s 8 Fragments mentions that “the city is a model… a space into which one astrally projects, a dream space” (Etchell, 1999, 78), a space which is neither here nor there. We create our own versions of the city by describing places with our own words and picking out the things that are important to us. My version or the city will be different to yours because I see different things to you. This helped to create an idea of an audio tour down the High Street using our descriptions and memories of places to guide the audience. However, what were to happen if we included someone the audience had to follow. We see people everyday on the street and “we pass each other like objects on a projection line” but using the “ strange fragments and endless possibilities of passing each other on the street” (Etchells, 1999, 79) we create a new thought of lives changing if you follow that one person.

Creating a three-minute piece gave us the opportunity to explore how we could fit pervasive media in to a dream landscape. We knew that sound was going to have a big part of creating a dream landscape. As a result, we started by recording the High Street as we walked down the hill. However, we had the audience close there eyes and listen to the High Street with Maddie’s voice posing questions into whether they knew the people they passed. The feedback we received was unexpected, with the audience liking the contrast between the busy High Street and Maddie’s voice, and the idea of closing the eyes. Closing their eyes helped create isolation and an ability to use their “descriptive names, literal names, names that refer to the use we made of their streets and not their official function” (Etchells, 1999, 78). Despite this, it also created liberation where they were not worried about what others think, they were able to see and do what they wanted because nobody could see them. It also created a deeper connection of trust that we were not going to harm them in any way and it liberated them from that fear.

Dreams

Researching into Freud’s dream theories, we discovered that this theme of liberation runs throughout. Freud found that dreaming “cures sorrow by joy, cares by hopes and pictures of happy distraction” (Freud, 1953, 83). We use dreams to overcome fears, however, Freud also believed that “a dream is a fulfilment of a wish” (Freud, 1900, 121) and maybe “if these wishes were verbalized, cure would follow” (D’Amato, 2010, 199-200). Freud’s findings lead us to want to lead people in a dream-like state down the High Street using audio like falling down a rabbit hole.

Audio Tours

Looking further into audio tours led us to A Sardine Street Box of Tricks and trying some of their tour techniques on our potential tour route. They recommend trying “a ‘static drift’- choose a spot to sit and let the street come to you” (Crab Man and Signpost, 2011, 30). After choosing a bench in the middle of the busiest part of the street we found that people are in their own world and don’t interact unless they know each other. Groups of people move past each other, only interacting if they know each. If they don’t know anyone, they walk silently and quickly. The majority of people ignore the buskers, Big Issue sellers and promoters with very few interacting to any serious degree. The next step was to “look out for and point out those things on your street that have left marks of there disappearance… the gap left can be a space for storytelling” (Crab Man and Signpost, 2011, 55). At the time of doing this, the street was under-going road works so big parts of the concrete were missing. However, as we carried on we started to pay attention to the smaller parts of the concrete. One slab was cracked, with a strange slice and gaps filled by another type of concrete. This led to us creating a new narrative around it and the possibility of fitting it around a myth of Lincoln.

In order to start work on our piece we wanted to collect sounds from the High Street that we could use in the tour. This started with audio from travelling down the High Street to the train barriers, from inside McDonalds to an old style till in a sweet shop. Each sound we collected could never be created in the same way due to different people and different timings. They created something new and as a result we decided we to use the audio in a different way to create a different kind of piece.

Soundwalking

After our shift in ideas, we looked into soundwalking. In particular a company called Soundwalk who are “an international sound collective” (Soundwalk, 2015). They produce “cutting-edge audio guides, mixing fiction and reality to provide an exclusive and poetic discovery of a city” (Soundwalk, 2015). As well as audio tours they create sound installations in different cities using sound fragments. In Gibraltar, they created a piece called The Passenger, in which long-range antennae’s and scanners were fitted in a house They recorded frequencies from along the shores of the Straits of Gibraltar. This resulted in a collection of “an infinite variety of sound fragments”(Soundwalk, 2011). These sound fragments “were pressed onto a unique set of custom-made vinyl records which contain the separate elements of the final sound piece” (Soundwalk, 2011). The sounds were put into a track and a voice was recorded over the top. Unfortunately, I do not know exactly what is being said due to the language barrier but the tone and mixture of sounds make the recordings engaging despite not understanding what I am being told.

A sample of the performance can be heard at: http://www.soundwalk.com/#/INSTALLATIONS/passenger/

Looking further into soundwalking we discovered that it is “an exploration of the soundscape of a given area using a score as a guide… to explore sounds that are related to the environment, and, on the other hand, to become aware of one’s own sounds” (Drever, 2009, 32). This has an interesting effect on the participants. After the soundwalk is over Drever describes “a collective resistance to break the silence… out a desire to prolong the experience” (Drever, 2009, 35). Listening to what is happening can be empowering and creates a sense of awareness that the participants were not aware of before. This awareness and captivating effect is what we would like to create. Something that has never been heard before and never will be heard again, captured on an iPhone and liberated from the space it was in. It would also be interesting to see if you removed it from it’s environment whether it would have the same effect in a different setting.

Editing

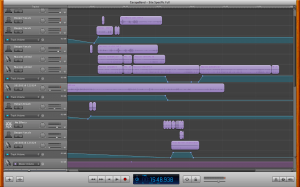

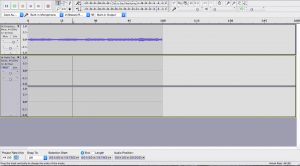

When we had decided our concept, we knew that editing was going to be difficult due to our lack of knowledge. However, we started by using Garageband to edit and slow down our recordings. After researching further we found that there were better forms of software that we could use. We looked into using Logic Pro X (a more advance form of software), however due to expenses and availability that was not a viable option. This led us to Audacity. Audacity is an editing programme that is available as a free download. It has more effects available than Garageband, yet can still work with Garageband to create the desired effect. As a result, we decided to use both to create our track.

We found various YouTube tutorials, which taught us how to do basic editing on Audacity and Garageband, and we built our skills up from there, by trial and error.

(Song Surgeon, 2011)

New Sounds

In order to create the piece we started by listening to the sounds we had collected and using different manipulations in Audacity to find anything that sounded interesting. Manipulations such as slowing down our coffee shop recording and adding a Wah Wah effect was particularly interesting. It gives the impression of water or a science-fiction noise and when listened to can be hard to believe that it started as a recording of a coffee shop.

As Lincoln has a railway line running through it, we could not have an audio experience of Lincoln without the train barriers or a reference to the trains. By recording the train barriers and slowing the down, adding reverb we created a loud and persistent noise which is able to collide with the slow and calming effect of the Coffee Shop Wah Wah.

Drafting Process

The first draft of our piece was very busy. There was no structure to it and when listened to, it did not go anywhere. However, it helped us to use and experiment with the software. In order to make it interesting to an audience it needed to still tell a story or go somewhere otherwise the audience is just listening to sounds. It was then suggested that we look into structuring the audio similarly to the way a symphony is structured. In particular, we looked into a ternary form: a three-movement piece in which the first movement is repeated after the second movement. Most symphonies follow a fast, slow, fast pace of movement, however we wanted to try a slow, fast, slow pace to see what the effect would be. We also stripped the piece back allowing space for the audience to hear and take in the sounds that were produced.

Conversely, the second draft allowed too much space. Not enough happened and there were spaces of nothing that lost the momentum of the piece. In consideration of this we created ‘build points’ in the track where it is almost unbearable for the audience to add anymore sound. This effect creates moments of peace and relief in the audio as well.

Evaluation

For our final performance we had 6 audience members due to time constraints. The performance was 16 minutes long and could only cater for one audience member at a time. Overall the response from the audience was positive with general appreciation for the sounds. When asked about the effect of the piece they were amazed at the effect of the dark room and how quickly they adjusted. They also liked the ‘collision’ of sounds. However, part of the audio did lose momentum through the middle section, which lost audience engagement.

Including a door text also worked well. This helped to explain to the audience what the performance was about and what they were listening to. Without it, they wouldn’t know that the sounds were Lincoln and it could have been confusing. The isolation of sounds in the audio also worked well in order to allow them to really hear what was created and was even found to be ‘relaxing’ during some of the slower movements.

Certain things could have been improved for the final performance, as the room was not completely dark. We made it as dark as we could on the day, however I would have preferred a completely blacked-out room. We also could have used our original idea of using blindfolds in order to create the dark, this would have also added to the theme of liberation. There is an incredible amount of trust that an audience member places in you when they are blindfolded and that would have been interesting to see.

If we were to perform the piece again, we would look into using a more advanced audio editing software in order to create a better quality of sound. We would also change a few edits on the track in order to prevent the loss of momentum and make the audio more interesting for the audience to listen to. The use of blindfolds and headphones would also be interesting to see and possibly guiding the audience member around a space so they start of somewhere and take off their blindfold somewhere else giving the impression that they have travelled through Lincoln.

Over the course of this process I have discovered that no two performances can be the same as the time, place and people are different. Site Specific in particular is “an unlikely and fleeting moment on the history of a place, known only through the traveller’s tales of those present” (Pearson, 2010, 194), it can unfortunately not be created again, however this makes the performance even more important in the way it is captured.

Bibliography

Crab Man and Signpost (2011) A Sardine Street Box of Tricks. Exeter: Blurb.

D’Amato, B. (2010) Aggression in dreams—intersection theories: Freud, modern psychoanalysis, threat simulation theory. Modern Psychoanalysis, 35(2) 182-204

Drever, J. L. (2009) Soundwalking: Aural Excursions into the Everyday. In: James Saunders (ed.) The Ashgate Research Companion to Experimental Music. Aldershot: Ashgate, 163-192

Freud, S. (1990) The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Volume IV The Interpretation of Dreams 1. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1900) The Interpretation of Dreams. London: Hogarth Press.

Lavery, C. (2005) Teaching Performance Studies: 25 instructions for performance in cities.

Pearson, M. (2010) Site Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pervasive Media Studio (2015) What is Pervasive Media? [Online] Bristol: Pervasive Media Studio. Available from http://www.pmstudio.co.uk/pmstudio/what-pervasive-media [Accessed 29th January 2015]

Song Surgeon (2011) Slow Down Music (Tempo Change) With Audacity Audio Editor [online video] Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CUxRdPn412E

Soundwalk (2011) The Passenger. [online] New York: Soundwalk. Available from: http://www.soundwalk.com/#/INSTALLATIONS/passenger/ [Accessed 12th May 2015].

Soundwalk (2015) About Us. [online] New York: Soundwalk. Available from: http://www.soundwalk.com/#/ABOUT/ [Accessed 12th May 2015].

Tapper, J. (2014) Pervasive Games: Representations of Existential In-Between-Ness. Themes in Theatre, 8, 143-161.